A little background

I wrote an essay a while back and I thought it’s interesting enough to put it here. I wrote it for my Academic Writing class, so sorry in advance, if the style is a bit dry. I tried to make it readable, but I understand not everyone will like this.

This essay was written in 2022, so some “recent” series I mentioned are no longer recent. The general premise was to look at female comic book characters through the lens of the feminist theory. As for the time frame, I focused on the Modern Age (since 1985). Also, I decided to not keep in-text citations. They’ll be included at the end if anyone is interested.

Anyway, enjoy!

Women in Fridges: Female Characters as Plot Devices in Graphic Novels

Introduction

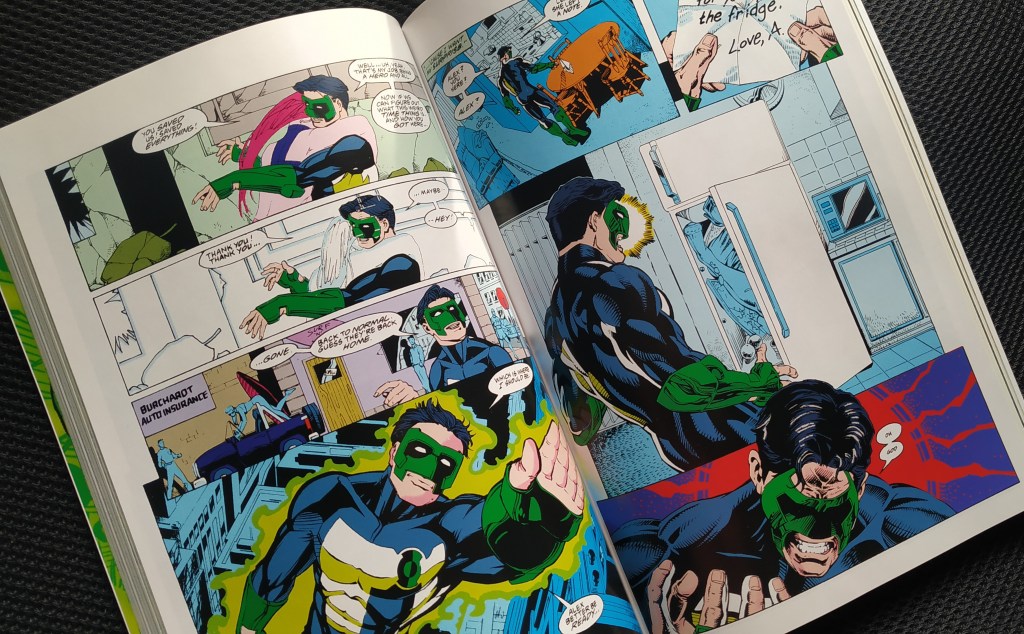

One day, after an exhausting day of fighting various villains, Kyle Rayner comes home. The first thing he sees, is a note on the table telling him to look for a surprise in the fridge. The note, seemingly written by Alex, does not lie. What awaits him is the biggest surprise of his life. The fridge is stuffed with his dead girlfriend. That shocking image takes up half of the page. Alex existed only for a few issues and now her time as a character has come. It was time to transform her into a plot device.

This event is the origin story of the phenomenon named as “woman in the fridge” by Gail Simone, a successful comic book writer (Deadpool, Wonder Woman) and an author of the website with the same name. The phenomenon itself is older than the event that gave it a name. Endangering, injuring or even killing of female characters in comics is as old as the medium itself. For the sake of clarity, this paper will focus on some of the more prominent examples from the Modern Ages of comics, which started in 1985. The first one will be Alex DeWitt, from the “Green Lantern” title, already mentioned above, who was killed. The next character, Barbara Gordon (the first Batgirl), did not die. Instead, she suffered for many years to come, after the traumatic events of The Killing Joke. The last example will be Lois Lane, who was one of the few victims of “fridging” in recent times.

Fortunately for female characters, the social changes and the feminist influence had an effect on the comic book industry. Gail Simone, as well as many other female creators were hired by two biggest publishers of mainstream superhero comics, DC Comics and Marvel. This, and noticing a large group of potential comic buyers in female audiences, led to decrease in incidents of female characters being put in fridges (whether literally or metaphorically). However, it did not eliminate it completely.

This paper will examine the issue of “fridging” female characters in comics from the perspective of the feminist theory. According to its entry in the Oxford Dictionary of Critical Theory, the feminist theory focuses on gender inequality, its origins and mechanisms, but also proposes a way forward both in the immediate future and the imagined one where the inequality has been abolished. Chris Weedon, in the first chapter of her book Feminist Practice and Poststructuralist Theory, describes the mechanism of conveying gender inequality and ingraining it in next generations, also through comics.

The Past

The Modern Age of comics is commonly accepted to have started in 1985, with the publication of “The Dark Knight Returns” and “Watchmen”. Despite the name, it can be considered “the past” for the purpose of this paper, as “fridging” was still prevalent in those times.

The comic book industry has always been dominated by male creators. Even the creation of Wonder Woman, the most well-known female character, is credited to a man, tough Marston’s wife and their lover’s influence must also be noted. Over forty years later there was little to no change. Writers and artists of the comics discussed in this section are all men. This fact is relevant because of the way gender inequality, including a model for femininity and female behavior, is integrated into society. According to Weedon, all of us as individuals are exposed to it though social institutions in different forms, such as family, schools, organized religion, and pop culture (which would include comics). This may explain why these creators perpetuate these patterns in their work.

It seems that even the more acclaimed writers like Alan Moore cannot escape it. After all, it was his story that maimed Barbara Gordon, one of the most prominent DC female characters. The Killing Joke (Moore and Bolland) was first published in 1988. It still remains a very important story to the Batman mythology as it reveals the origin of the Joker, Batman’s nemesis. It is still being reprinted in different editions, such as the deluxe edition (which is characterized by oversized format) and as part of the “Batman Noir” line, which serves as evidence of the story’s success. In it the Joker comes to Barbara’s apartment and shoots her in the spine, which causes her to become paralyzed for the next twenty-three years. It is stated in the dialogue that the Joker stripped her of her clothes and took photos of his ‘work.’ He later showed them to Commissioner Gordon, Barbara’s father.

To this day, The Killing Joke remains one of the most graphic incidents of violence towards a female character. The role of Batgirl was taken away from Barbara together with the use of her legs. She was not given an opportunity to regain her superhero identity until over twenty years later, when Gail Simone took over the Batgirl title. It is worth noting that when Bruce Wayne suffered a similar injury not only did he not retire from being Batman, but also recovered in considerably less time, within the Knightfall storyline (published from 1993 to 1994). Barbara’s injury was permanent at the time, though it did not stop her from staying true to her identity as an individual and continuing her superhero work as Oracle. Despite the attempts to marginalize her, Barbara became arguably the most important Bat-affiliated character, as her new role required her to coordinate actions of all other Batfamily members (including Batman himself) and utilize her genius-level IT skills.

What makes the maiming of Batgirl a “fridging” incident is the fact that she was shot, as the Joker put it, “to prove a point” and to drive her father mad. Her suffering and the violence against her was just a means to an end. However, through the efforts of many next writers to handle her character, it was turned around to serve her own development as a superhero and as an individual woman.

The same cannot be said about Alex DeWitt, whose fate gave name to the phenomenon discussed here. She first appeared in Green Lantern #48 in 1994 as a photographer and Kyle Rayner’s girlfriend. In issue #54, after enough time has passed for the readers to get to know and like her, she died. It happened in a particularly brutal manner. She was choked to death and stuffed in the fridge. However, contrary to popular belief Alex was never dismembered. Ron Marz, Alex’s creator, stated in his response to Gail Simone’s list that the Comics Code Authority saw the image of a body in the fridge as too gruesome for the readers. The page had to be redrawn to be less revealing, and thus leaving more to imagination. He continues to reveal that Alex was created to die. She did not become a plot device; she was born as one. According to Marz, her death was meant to make Kyle realize the more serious implications of being a superhero. Almost thirty years later Alex remains mostly dead, although occasionally brought back as a zombie (during the Blackest Night event) or a part of Kyle’s imagination (in the Circle of Fire story).

Alex’s death was so outrageous, that it prompted Gail Simone to compile a list of incidents of violence towards women in comics and publish it on her website (in 1999). Though it appears to be inactive now, the list is still long and contains some of the most prominent female characters. Simone also included a “respondent list”, which includes comic book creator’s reactions to the “Woman in the Fridge” phenomenon.

The Present

The actions taken by Simone brought attention to the issue of gender inequality in comics as a medium, and indirectly in the comic book industry. It was a sign of ongoing changes in the society. Hiring female comic book creators is a common occurrence now.

Unfortunately, there are still some residual traces of “fridging” left. One of them is the case of Lois Lane in Injustice: Gods Among Us. Initially a series which started as a promotional piece for the video game under the same title, it has since outgrown its origins and is currently collected in two omnibuses. It would be a fair assumption that a series published in 2013 would not put any female character in the fridge, given the social changes that occurred since 1999. Yet, pregnant Lois dies a brutal death at the hands of Superman, after the Joker drugged him to see her as Doomsday, Superman’s most dangerous enemy.

Injustice tells the story of Superman’s descent into madness and paranoia after the death of his family, as he attempts to stop all crime in the world. He is joined by some members of the Justice League. Their efforts lead to the creation of a totalitarian regime led by Superman himself. From a storytelling perspective, all this was made possible by the sacrifice of Lois Lane. Additionally, Lois’ pregnancy ingrains a certain type of femininity in the readers of this comic, despite the fact that Tom Taylor seems to be aware of it. Lois confronts Superman about this very issue when he hears the baby’s heartbeat and immediately demonstrates over-protectiveness towards his wife.

However, Lois’ death can perhaps be seen as an isolated incident, even in the series. Other female characters seem to receive much better treatment from the writers. Harley Quinn is given a personality, allowed to exist on her own, separate from the Joker and even join Batman’s resistance against the regime.

Changes can also be seen in the comic book industry. Today DC Comics presents its female characters with respect they deserve. Even minor characters from the past are being brought to the front. One such example an Amazon warrior Nubia who was recently given her own limited series and crowned the queen of the Amazons. It is also worth noting that in addition to being a woman, Nubia is also a Black character. DC’s prominent featuring of characters who are diverse in many ways is growing influence of intersectional feminism on comics. At the same time new female characters are being created, and they are written by female writers. Among them are Yara Flor, a new Wonder Woman from the Amazon rainforest introduced in the Infinite Frontier event, created by Joëlle Jones; and Sojourner “Jo” Mullein, a Black Green Lantern who operates primarily in deep space, written by N. K. Jemisin. Both characters were created within the last two years.

Conclusions

Superhero comics as a genre came to existence in 1938 with the publication of Action Comics #1. Since then many women were put in fridges, especially in the Golden Age, before Frederic Wertham’s book Seduction of the Innocent caused the Comic Code Authority to be created and limited incidents of explicit violence in comics. The CCA’s influence over comics is visible even in the early Modern Age. It is because of its censorship that the brutal manner of Alex DeWitt’s death is left mostly to the reader’s imagination.

As Weedon explains, the influence of institutions (which include pop culture) is immense and it alters the way people perceive reality. This is also true for comics, which is why eliminating or even limiting the spread of the “women in refrigerator” phenomenon is so crucial. Using an act of extreme violence against a female superhero “to prove a point” will alter the public perception of that female character, especially when their male counterparts seem to suffer little to no consequences after experiencing similar violent acts.

Despite this, the future of comics look bright. The social changes and influence of feminism on the comic book industry is becoming visible. Creators of diverse backgrounds are hired by major publishers to create diverse characters. It is a future where comics truly are for everyone.

Bibliography

Time to give credit to everyone I cited in this text. Thank you! I can write this here, since it’s a blog post and not an assignment. Hehe.

- Buchanan, Ian. A Dictionary of Critical Theory (Oxford Quick Reference) (p. 168). OUP Oxford. Kindle Edition.

- Curtis, Neal and Valentina Cardo. “Superheroes and third-wave feminism”, Feminist Media Studies, 18, no. 3 (2018) 381-396, DOI: 10.1080/14680777.2017.1351387

- The Oxford Handbook of Feminist Theory, Edited by Lisa Disch and Mary Hawkesworth, published online, 2015, DOI:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199328581.001.0001

- Marz, Ron (writer) and Willingham, Bill (artist). Green Lantern: Kyle Rayner vol.1. Edited by Paul Santos, Burbank: DC Comics, 2017 .

- Moench, Doug (writer); Aparo, Jim (artist); Roy, Adrienne (colorist). “Batman #497.” In Batman Knightfall Volume One. Edited by Jeb Woodard, 333-338. Burbank: DC Comics, 2012.

- Moore, Alan (writer) and Bolland, Brian. Batman: The Killing Joke: The Deluxe Edition, New York: DC Comics, 2008.

- Nelson, Kyra. “Women in Refrigerators: The Objectification of Women in Comics”, AWE (A Woman’s Experience): Vol. 2 , Article 9, 2015.

- Simone, Gail. “Character list”, Women in Refrigerators, https://www.lby3.com/wir/women.html

- Taylor, Tom (writer) and Miller, Mike. Injustice: Gods Among Us Year One, New York: DC Comics, 2016, issue 3.

- Weedon, Chris. Feminist Theory and Poststructuralist Theory, Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1997.

Leave a comment